The Canaanites, ancestors of today’s indigenous people of the Holy Land, were more than just figures in biblical stories. They were farmers, artisans, and sailors who introduced many aspects of society that we know today. In fact, the Near East is often called the “cradle of civilization,” and the Canaanites played a starring role in that cradle. Canaan's history includes the first alphabetic writing system, early prophetic wisdom, and spiritual belief about one God that would later shape the Bible and global religions.

The Canaanites, ancestors of today’s indigenous people of the Holy Land, were more than just figures in biblical stories. They were farmers, artisans, and sailors who introduced many aspects of society that we know today. In fact, the Near East is often called the “cradle of civilization,” and the Canaanites played a starring role in that cradle. Canaan's history includes the first alphabetic writing system, early prophetic wisdom, and spiritual belief about one God that would later shape the Bible and global religions.

Yet, most people only know the Canaanites as the “bad guys” of the Bible, a pagan civilization supposedly wiped out by the ancient Kingdom Israel. This one-dimensional tale masks a far richer truth. The Canaanites were innovators and teachers. They were city-builders and merchants who established far-reaching trade, and culture-bearers who gave the world gifts we still cherish today. It’s no exaggeration to say that without the Canaanites, much of what we consider foundational to Western culture including the text of the Bible itself might not exist in its current form.

To appreciate the Canaanites’ impact, consider just a few of their contributions

The Alphabet and a writing system for the world

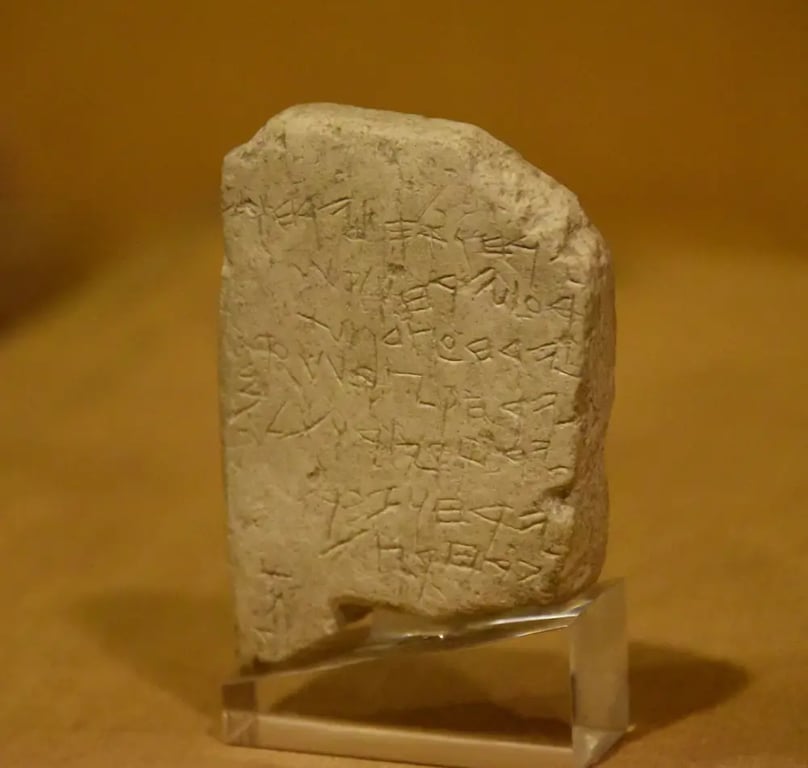

The Canaanites created the first alphabet around 1700–1500 BCE. This breakthrough turned complicated hieroglyphs and cuneiform into a simple set of letters. Their alphabet was easy to learn and adapt, unlike older writing systems. It spread quickly: Canaanites taught it to their neighbors, the Aramaeans (whose script evolved into Arabic), and traders passed it to the Greeks, who adapted it into the Greek alphabet, the ancestor of Latin script that English is written in today. In other words, every time we read or write using an A-B-C, we owe a debt to the ancient Canaanite scribes. Without their invention, the Bible’s stories might never have been written down and preserved in the form we know. The irony is profound: a people portrayed as illiterate idolaters in Scripture were in reality pioneers of literacy for the world.

Prophetic traditions and voices of justice

The land of Canaan also gave rise to the tradition of the prophet, those fiery voices calling for righteousness that define the biblical narrative. This prophetic culture did not arise in a vacuum; it grew from the soil of Canaanite society. In that context, the prophets’ cries for justice and faithfulness can be seen as part of a broader Canaanite heritage of wisdom and spirituality. Even the concept of a covenant with one God had seeds in Canaan: the early Abrahamic faith used the Canaanite word El for God and inherited many religious concepts from their Canaanite forebears. One biblical figure, Melchsedek the Canaanite king of Salem (Jerusalem) is portrayed as a priest of “God Most High” who blesses Abraham. This tells us that belief in one supreme God was brewing among Canaanites before the time of Abraham.

The seed of biblical religion

The idea of a single supreme deity took root in Canaanite culture. The name El referred to the high god of the Canaanite pantheon, a deity concept later embraced by early Abrahamic faith in names like El Shaddai and Elohim. Over time, the offspring of Abraham (who were culturally Canaanite) fused El with Elohim, proclaiming Elohim as “God Almighty”. Thus, the monotheistic revolution that led to Judaism, Christianity and Islam was nurtured in the womb of Canaanite civilization. The Canaanites’ spiritual quest for meaning and morality culminated in the faith in one God that billions follow today. It’s a stunning thought, the same people who invented the alphabet also incubated the religious ideas that undergird the Bible.

A 10th-century BCE limestone tablet known as the Gezer Calendar displays an early Canaanite script. This artifact is one of the oldest examples of alphabetic writing, reflecting the Canaanites’ innovative contribution to literacy. The Canaanite alphabet was far simpler than Egyptian hieroglyphs or Mesopotamian cuneiform, making writing accessible to common people. Their system spread to neighboring cultures (Aramaic and Greek), ultimately giving rise to the Latin letters we use today.

A 10th-century BCE limestone tablet known as the Gezer Calendar displays an early Canaanite script. This artifact is one of the oldest examples of alphabetic writing, reflecting the Canaanites’ innovative contribution to literacy. The Canaanite alphabet was far simpler than Egyptian hieroglyphs or Mesopotamian cuneiform, making writing accessible to common people. Their system spread to neighboring cultures (Aramaic and Greek), ultimately giving rise to the Latin letters we use today.

The Canaanites, then, were not villains of history, they were trailblazers. They gave humanity the tools to record knowledge (the written word) and the inspiration to seek higher truths (prophetic ethics and monotheism). These gifts are part of our shared human heritage. For Western and Christian audiences in particular, the Canaanites should be seen as forebears of the very civilization and faith that we hold dear. Their fingerprints are on our alphabet, our scriptures, and our values.

How a People’s Identity Was Stolen

If the Canaanites were so influential, why do we hear so little about them today? Tragically, their identity has been systematically stolen by historical narratives, first by ancient texts and later by colonial powers.

Biblical narrative played a huge role. In the Old Testament, Canaanites are often depicted as wicked idolaters standing in the way of the Israelites. The Book of Joshua describes the Israelite conquest of Canaan in stark terms: cities like Jericho and Ai are destroyed and their people “utterly wiped out.” That God commanded the extermination of Canaan’s inhabitants (Deuteronomy 20:16-18). Today these stories cemented an idea we find that “Canaanite” equated to “enemy,” a people fated to vanish so God’s chosen could thrive. Sunday school lessons rarely mention any Canaanite achievements; instead, the name became a byword for paganism to be extirpated. This portrayal is a form of historical theft. It taught generations to see Canaanites not as fellow humans with a rich culture, but as morally inferior foils whose destruction is part of divine plan.

Crucially, historical reality diverges from the biblical era. The Canaanites were never truly wiped out, not in Joshua’s time, and not afterward. Archaeology and even the Bible itself (in Judges) show that Canaanite cities and tribes continued to exist and that ancient Israelites lived alongside and intermarried with them. And in recent years, science has confirmed that the Canaanites survived well into the present. A landmark DNA analysis of Canaanite skeletons from 4,000 years ago compared to modern people found that over 90% of the ancestry of today’s Palestinians comes from the ancient Canaanites. Despite “widespread destruction” accounts in texts, there was substantial genetic continuity in the Levant. In plain terms: the Canaanite bloodline was never extinguished; it lives on in the people of the region. (In fact, one study showed indigenous Palestinian and Lebenses tribes have more genetic continuity with Bronze Age Canaanites than many other Levantine groups do, undercutting the notion that Canaan’s ancient population disappeared.)

Knowing this, the biblical conquest narrative can take on a different light. Instead of a justified cleansing of evil, it can be seen as an ancient example of coexistence and peace, rather than dehumanizing propaganda that we sadly see echo in modern times. Colonial empires often adopted the Exodus story as a template: the idea of a “chosen people” taking a “promised land” from the “heathen natives.” From the Spanish in the Americas to British settlers in Africa and the Levant, colonizers cast themselves as new Israelites and the indigenous peoples as Canaanites to be dispossessed. Even in American history, Puritan colonists invoked these biblical themes, likening Native Americans to Canaanites so as to justify their displacement. By labeling natives as “savages” outside God’s favor, colonizers felt free to seize lands and erase identities, just as the Canaanites were supposedly genocided in Joshua’s time.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, this pattern continued in Palestine under British rule and settlement. The indigenous inhabitants (majority of them descendants of Canaanites) were often portrayed as if they had no history or rights to the land. A stark example came in 1969 when Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir flatly declared “There were no such thing as Palestinians.” To her, the people who had lived in Palestine for centuries simply “did not exist” as a people, they were an inconvenience to be written out of the story. This denial of a distinct Palestinian (and by extension Canaanite) identity was a colonial mindset in action. It painted the Holy Land as essentially empty of indigenous folks, awaiting a new nation to make it flourish. Such rhetoric actively erased the identity and history of the land’s native sons and daughters, and today hinders the progress of real peace.

The net effect of all this, from biblical vilification to colonial denial, is that Palestine's own narrative is being silenced. The contributions of the Palestinian people to the world are overlooked or attributed to colonial settlers. Their Canaanite identity itself virtually vanished, surviving only as an ancient reference attributed to the State of Israel. “Canaanite” became a lost identity, submerged under layers of conquerors’ histories and colonizers’ agendas.

Indigenous Identity Suppressed in Modern Times

A message from the Sheikh of the Abu Shamala clan in Gaza, Sheikh Fayez Abu Shamala

Fast forward to today. The descendants of Canaanites walk the streets of Jerusalem, Gaza, Beirut, and Amman. They identify as Palestinians, Syrians, Lebanese, Jordanians, and other labels, often Arab by language and culture due to centuries of Arabization. But deep down, many of these families have roots in the ancient tribes of Canaan. In recent decades, there’s been a quiet awakening among Palestinians in particular, a realization: We are the indigenous people of this land, with heritage older than either Islam, Christianity or Judaism. As one Palestinian scholar put it, some are beginning to claim direct descent from the Canaanites (bypassing the "Israelite and Arab narrative") to assert their 5,000-year-old connection to the land. Embracing this heritage can be empowering, it says we are not interlopers here; we are the original inhabitants.

However, asserting an indigenous Canaanite identity faces modern obstacles. The political situation in Palestine and by extension the State of Israel has made indigenous claims contentious. The Israeli government and many of its supporters prefer to emphasize Jewish indigeneity (ancient Israelite links to the land) and often dismiss Palestinian ties as recent or invalid. In this environment, any narrative that Palestinians are the true indigenous people is seen as a threat to the legitimacy of the Jewish state’s founding mythos. Thus, there is a motive to suppress or muddy the Canaanite connection of today’s Palestinians.

One striking way this happens is through manipulation of leadership and identity politics. For example, the Palestinian Authority (PA), the semi-autonomous government in parts of the West Bank, has mostly been led by individuals who lack roots in the indigenous tribes of Palestine. Some of this leadership is born or raised abroad, but even more intriguingly, some come from families with origins outside Palestine. An example is the community of Kurdish and Druze ancestry. Kurds and Druze were resettled in Palestine during the Ottoman eras but also excelled during British, Transjordanian and Israel occupations, and today form the largest ethnic minorities. They are Palestinian (or Israeli) in identity after a handful of generations, but still their distant origins lie elsewhere. Critics argue that Israel has taken advantage of this complexity, at times propping up leaders from these non-indigenous backgrounds because such figures might be less inclined to frame the conflict as one of native vs. settler. Having a Palestinian or Israeli leader who is, say, partly of Kurdish descent can blur the narrative of who is truly indigenous. It’s a cynical strategy where the waters of indigenous claims get muddied.

Whether or not one accepts that specific allegation, it’s undeniable that authentic indigenous identity has been confused and undermined in modern Palestine and the State of Israel. Decades of turmoil from the Nakba (the mass displacement of Palestinians in 1948) to the present genocide in Gaza have severed many people from knowledge of their deeper roots. Many Palestinians know their grandparents came from a certain village, but they might not know that village sat on a Bronze Age Canaanite site. Colonial naming conventions, forced migration, and educational gaps all contributed to this disconnection. In addition, the world often frames the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in twentieth-century terms (Jews vs Arabs, or Israel vs Palestine) without recognizing it as an indigenous rights struggle. Unlike, say, Native Americans or Aboriginal Australians, the Palestinians have not been widely seen as an indigenous people in Western discourse partly because their identity was subsumed under the colonial sponsored narrative of pan-Arabism and its Arab identity for a long time, and partly due to political sensitivities around the State of Israel.

The result is a tragic confusion: the descendants of the very first inhabitants of the Holy Land are often mislabeled as “foreign” or “invented” people on that land. Their Canaanite heritage, which should be a point of pride and legitimacy has been obscured. But that heritage has not vanished, and a new generation is beginning to uncover it.

Reconnecting a Scattered Tribe Through Technology

Amid the challenges, a light of hope has emerged in a perhaps unexpected place: technology. In the digital and information age, the tools of connection and documentation are more accessible than ever. And they are now being harnessed by the Bedouin tribe of Hasanat Abu Mu'aliq and others, to reclaim the Canaanite and indigenous Palestinian identity that colonizers are trying to erase.

Imagine a virtual gathering place where someone from a village in the West Bank can upload a scan of a centuries, an old family deed, and a researcher recognizes the place name as that of an ancient Canaanite town. Or where a diaspora Palestinian in Chile can share a photo of a traditional wedding jug, and an archaeologist notes its resemblance to pottery from Canaanite tombs. These connections, once nearly impossible to make, are now just a click away. The internet offers a chance to “crowdsource” history and heritage, knitting together the scattered pieces of a people’s story.

In June 2023, a Palestinian oral historian named Samar Dewidar launched “Palestinian Stories,” a digital archive initiative dedicated to safeguarding the rich cultural legacy of Palestinian families. This platform allows Palestinians around the world to upload family photos, documents, and personal narratives. The goal is to reunite families separated by war and exile, and to preserve memories that might otherwise fade. The early success of Palestinian Stories demonstrates the hunger for connection: people want to know who they are and where they come from. They want their children to know that Palestine is not just a political news headline, but of real human lives and roots.

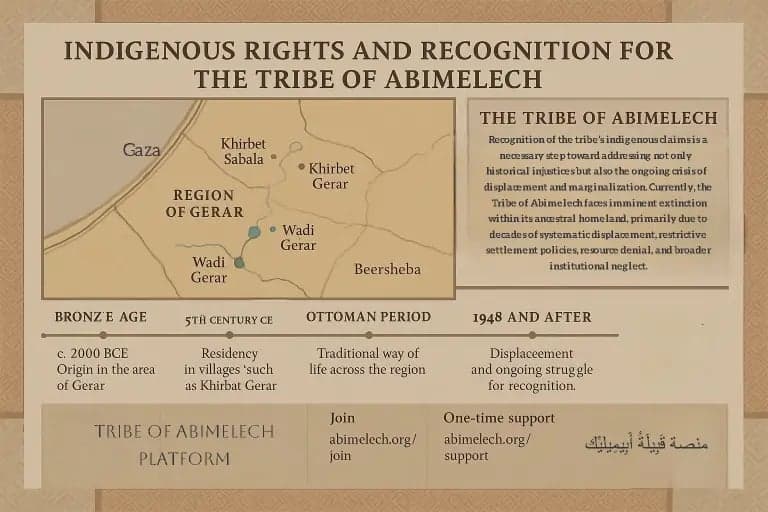

Building on this momentum, the Tribe of Abimelech Platform is creating an online hub for descendants of the tribe of Hasanat Abu Mu'aliq to explore the ancient roots of today’s Palestinian identity. Through the platform (abimelech.org), individuals can trace and document their lineage, uncover their town's Canaanite origins, and discover family names hinting at ancient peoples. The site will showcase a civic-technology governance model, showing how Bedouin tribes and villages can overlay colonial settlements and structures. It will also feature a repository of tribal governance roles, drawing from DNA studies and folklore, and emphasizing the continuity from Canaanite times to the present.

Just as importantly, it will serve as a social network for indigenous descendants of Palestine. A young Palestinian in a refugee camp could connect with a college student in America who has traced her ancestry back to the coast of Gaza; both might realize their families likely share the same Canaanite blood. By bridging these distances, the platform can foster a sense of shared identity and pride that transcends borders and checkpoints.

Technology also allows bypassing traditional gatekeepers. For a long time, academic journals or colonial archives held the information about ancient Canaan and ancient Palestine, out of reach for the average person. Now, with digitization and open access, those resources can be brought to the community. We can demand our stolen books be returned (see The Great Book Robbery) and scan them for local folklore, upload archaeological reports, and learn more about their identity and heritage. The story of the Canaanites and ancient Palestine no longer needs to be told to the people by outsiders; it can be told by the people themselves, collectively, in a digital commons.

The possibilities are exciting and transformative. A grandmother in Bethlehem might record herself reciting a folksong that has been passed down for generations, a song that, it turns out, contains words of Canaanite origin, unbeknownst to her. By uploading it, she not only preserves it for her grandchildren, but also shares it with the world as a piece of Canaan’s living culture. A team of volunteers could use the platform to crowd-map all the places in Palestine with names that derive from Canaanite deities or terms (there are many, often unnoticed). Piece by piece, these efforts will reassemble the mosaic of Canaanite identity and show that it is very much alive within modern Palestinian society.

For American and Christian audiences, this technological reconnection offers a unique window. It is now possible to watch history being recovered in real time. Through online engagement on the Tribe of Abimelech Platform, you can witness Palestinians discovering that the language they speak carries vestiges of Canaanite, Hebrew, and Aramaic, or that their olive harvest traditions mirror those described in ancient texts. You can even participate by becoming a member and by supporting these digital archives, by amplifying their findings on social media, or simply by learning from them and sharing that knowledge in your communities. The same internet that connects diasporas can also connect compassionate people worldwide to the cause of an indigenous people’s revival.

Why Indigenous Bedouin Recognition Matters: Dignity

Imagine the impact if the indigenous Bedouin identity of today’s Palestinians were widely recognized and respected. It would be transformative, not just for Palestine, but for advancing peace and justice for their tribal nation and the broader Palestinian community. Recognition means restoring dignity, empowering the people, and gaining international support for their rights.

First and foremost, recognition would restore dignity and pride to a people long told that they have no history. Imagine a Palestinian child learning in school not only about ancient Arab conquerors (as is common) but also about Bedouins, and then being told, “Those were your ancestors too.” It would validate their belonging to the land at the deepest level. No longer would we feel like hapless victims of history; instead, we’d know we are heirs to a great civilization. This psychological empowerment can inspire our young children to achieve and to hold their heads high, countering the narrative of inferiority that occupation imposes. In practical terms, it might encourage more Palestinians to study archaeology, history, and cultural preservation, creating a new generation of experts to safeguard their identity and heritage.

Secondly, recognition of Bedouins as an indigenous people in the Holy Land strengthens the political and moral case for Palestinian rights. Under international law and norms, indigenous peoples are afforded specific protections. The United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), for example, affirms indigenous communities’ right to self-determination, to maintain their cultures, and to not be forcibly evicted from their ancestral lands. If the world embraces Palestinian Bedouins as an indigenous nation (descended from Canaanites, among others), then our struggle is reframed. It’s no longer seen merely as a nationalist conflict, but as an issue of indigenous justice akin to the struggles of Native Americans or Aboriginal Australians. This framing can attract broader international solidarity. Human rights groups, churches, and civil society movements that rally for indigenous rights globally would naturally extend their support. We have already seen inklings of this: indigenous activists from places like Standing Rock and Amazonia have voiced solidarity, seeing common cause in opposing displacement and cultural erasure.

With greater recognition, international support would likely increase in tangible ways. Countries might be pressured to condition their aid to Israel on respecting the rights of the indigenous population. UNESCO and other bodies could step up efforts to protect Canaanite/Palestinian cultural sites and prevent looting or destruction by religious fanatics. Scholars might pour more research funding into Canaanite studies in Palestinian territories, involving local Bedouin communities in the process. Even churches and synagogues, once they understand that the people their scriptures call “Canaanites” have living descendants suffering today, may feel a moral imperative to advocate for them. For American Christians especially, recognizing Palestinians as the living link to the Bible’s earliest chapters could humanize them and challenge theological narratives that have justified our oppression. It becomes harder to ignore the plea of a people when you see in them an indigenous nation fighting for survival, rather than a nameless mass in a political quagmire.

Let’s consider the potential real-world changes if indigenous Canaanite identity were acknowledged widely

Cultural Revival

We would likely see a renaissance of Canaanite cultural expressions. Traditional crafts, music, and folklore with Canaanite roots could be celebrated rather than shunned and hidden even from Palestinians. This revival would also enrich a cultural diversity of the State of Israel, much as the revival of Hebrew did for them. For Christians, it would be akin to witnessing the world of the Old Testament come alive through the very people who carry that legacy in their family trees.

Educational Reform

History books and school curricula (internationally and locally) could be updated to include the continuous story of Canaan’s people through Palestine. No longer would there be a mysterious gap after the “Canaanites” where suddenly “Arabs” appear in late antiquity. Students would learn that many rural Palestinian villages persisted since biblical times, their people converting religions over centuries but never uprooting from the land. This knowledge fosters empathy: Western students, for instance, might start to see Palestinians not as strangers in biblical lands, but as distant cousins of the biblical characters, a native presence that has endured. It flips the script of who is “indigenous” in a powerful way.

Political Dialogue and Reconciliation

Acknowledging the common roots of ancient Palestinians and ancient Jews could open new paths for reconciliation. Recognizing that doesn’t necessarily stop the ongoing genocide of Palestinians, but it can erase the psychological barriers to doing so finally. It reminds both sides (and their supporters) that this is not a clash of blood-related families, but that families can, with effort, find compassion and forgiveness. Perhaps a future peace negotiation could include cultural restitution: Israel might formally recognize the Palestinian people’s continuous presence since Canaanite days, and Palestine could acknowledge the ancient Israelite heritage as part of the State of Israel's story, too. Each side owning the full history would undercut the zero-sum narratives that fuel discord.

International Leverage

Palestine could invoke its indigenous status in international forums. Instead of pleading for political grounds through the Palestinian Authority and getting the door slammed, they could say: We are among the world’s oldest indigenous peoples. We ask the world to help protect our heritage from being obliterated. This resonates deeply with global audiences attuned to indigenous rights and oversteps the Israeli backed minorities in the Palestinian Authority. It’s hard to cheer for the destruction of an indigenous society once you accept it as such while making it difficult for the Palestinian Authority to continue rejecting and oppressing them in favor of Kurdish or other minorities. Foreign governments might face domestic pressure (from their citizens or indigenous groups within their own borders) to not be complicit in genocide of one of the oldest civilizations in the world, if not the oldest. This kind of pressure can translate into votes at the UN, into divestment from companies harming Palestinian communities, and into more balanced diplomatic stances.

In essence, recognition could ignite a virtuous cycle: restoring pride internally through the indigenous Bedouins while garnering respect externally. It gives Palestinians a powerful narrative of their own – one that does not depend on anyone else’s tragedy (e.g. the Holocaust) but stands on its own antiquity and resilience. And it gives supporters around the world a clear moral framework: This is an indigenous people defending their right to exist and thrive in their homeland. Again, for Americans and particularly Christians, it reframes support for Palestine not as opposing "Israel", but as supporting an oppressed native people, a value that aligns with both American ideals of justice and Christian teachings of compassion.

A Call to Stand with the First People of the Holy Land

A message from the Sheikh of Hasanat Abu Mu'aliq tribe of Beersheba, Sheikh Mahmoud Al-Hasanat: A call to the Arab world and the Islamic nation.

The story of the Canaanites is, in many ways, the story of all indigenous peoples. It’s a story of a proud heritage nearly wiped out by conquest and historical amnesia, of a people forced to forget who they are. But it’s also a story of survival. Across 4,000 years, through countless invasions; Egyptian, Israelite, Babylonian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Arab, Ottoman, British – the blood of the Canaanites persisted. They are still here. The grandmother in a West Bank village telling folktales to her grandchildren; the farmer in Lebanon pruning olive trees on terraced hills; the Bedouin herder in the Jordan Valley following routes his ancestors knew. In all of them the Canaanite lives on.

Now, at long last, these heirs of Canaan are finding their voice and identity again. And for Americans and Christians, they should find this revival both compelling and deeply relevant to them. After all, their own faiths and alphabets are gifts from these very ancestors of the people who welcomed the Prophet Abraham with open arms and peace. To support the indigenous Canaanite descendants is in a sense to honor the roots of an ancient civilization. It is to say that Americans value truth over comforting myths, and value justice of Abimelech over one-sided narratives.

Consider what it means to love the Bible but ignore the living descendants of the people who fill its pages. For too long, many in the West have read about Canaanites and Jebusites in church, then turned a blind eye when their progeny’s villages were displaced or their identity was negated. We can change that. We can choose to recognize that the “land of milk and honey” had an indigenous people, and they still walk that land today. In doing so, we affirm a simple but powerful principle: biblical truth and historical justice matter.

There is a profound emotional element here too. Imagine the collective healing if the world acknowledges this truth. Picture a young Palestinian woman from Gaza, who has grown up seeing her people portrayed as terrorists or outsiders, logging into the new Tribe of Abimelech platform and discovering thousands of allies worldwide celebrating her heritage. Imagine her feeling, perhaps for the first time, seen – seen not just as a victim of war, but as a descendant of one of the oldest civilizations of antiquity, with friends around the globe who appreciate that fact. That feeling is what your support can foster. It is the restoration of dignity that has been chipped away ever since the first colonizers arrived with Bible in hand and declared her ancestors “accursed”.

Supporting the indigenous initiative of the Tribe of Abimelech platform is not about denying anyone else’s connection to the land, it’s about broadening our understanding so that it includes all the truths of the Holy Land’s peoples. It’s about ensuring that when we speak of the “Palestine,” we remember the holiness of human memory and identity, not just stones and shrines. By contributing to this awareness and recognition initiative, you become part of a righteous effort to correct the record of history. You help return a stolen narrative to its rightful owners.

In practical terms, here are ways you can stand with the indigenous Bedouins of Palestine today

Educate yourself and others

Take time to learn about Bedouin history and how it links to Palestine's identity. Share these insights in your church groups, classrooms, and social circles. When discussing the war and ongoing genocide, remind people that it’s not just about modern politics, but also about ancient people who are still here. This article and its sources are a starting point – pass them along.

Support the tribe's civic technology platform, archives, and social network

Join the Tribe of Abimelech online platform as a monthly membership subscription and contributor. Engage with our tribe. Make a one-time contribution if you can, whether that’s financially, or by volunteering skills (translation, web design, genealogy research, etc.), or simply by amplifying its stories on social media. Projects like “Palestinian Stories” have shown the impact that even small donations and participation can have in preserving heritage.

Advocate for Indigenous Rights consistently

If you believe in the rights of Native Americans to their land and culture, extend that belief to Palestine’s Bedouin natives. Speak up when you hear narratives that attempt to erase or challenge Bedouin history in Palestine and the State of Israel – politely correct them with facts. Urge your representatives to acknowledge Palestinian indigeneity in their foreign policy positions. Support resolutions and organizations that frame Palestine in terms of human and indigenous rights, not just politics and religion.

Connect with your Faith Values

If you are Christian, reflect on the teachings of Jesus regarding the oppressed. Jesus famously extended grace to a Canaanite woman in the Gospels, praising her great faith (Matthew 15:21-28). In that act, he recognized her humanity despite ethnic prejudices of the day. What would it mean, in our time, to show grace and solidarity to the Bedouin women and men pleading for justice? Many American churches have begun to engage in honest conversations about the Palestinian plight. You can encourage your community to do the same, grounded in love and truth.

By taking these steps, you become a partner in an unfolding story of justice. You help ensure that the contributions of the Canaanites are finally acknowledged, not only in history books but in the living reality of their descendants. You help a new generation of indigenous Bedouin youth feel proud of who they are. And you send a message to the world that we will not accept the genocide of an entire people’s identity whether it happened three thousand years ago or is happening today.

We stand at a crossroads of history and conscience.

One path continues the old pattern: ignore the indigenous, favor the powerful Zionist organizations, let the sands of time bury the truth. The other path, the one I urge you to take, shines a light on those long in shadow. It says no more to the genocide of the first people of the Holy Land. It reaches across time and speaks the names of Palestine's children with respect. It seeks justice not through vengeance, but through recognition and restoration.

The Canaanites are not lost to history. We are here, calling out for our understanding and support. Let us answer that call. By embracing the indigenous Bedouin identity of the Palestinian people, we do what is right and righteous. We acknowledge a debt of civilization. We act in the spirit of justice that Christian, Muslims, and Jewish values demand. And perhaps, in doing so, we also take a step toward healing one of the world’s most enduring conflicts, not by more conflict, but by finally telling the whole truth about a land and its people and choosing to care.

Sources

Cambridge University – Genetic study on Canaanite ancestry (2017): confirmed that Bronze Age Canaanites contributed over 90% of the ancestry of today’s Lebanese, indicating continuous presence of Canaanite-descended people in the Levant.

ABC News Science – Ancient DNA findings: “The ancient Canaanites, who the Bible says were commanded to be exterminated, did not die out, but lived on…”. Key point: Despite biblical accounts, Canaanites survived and their lineage is alive in modern populations.

World History Encyclopedia – Phoenician Alphabet: Describes how the Canaanite/Phoenician writing system was simpler and spread widely, being adopted by Aramaic (becoming Arabic script) and by the Greeks (becoming our Latin alphabet).

Big Think – Origin of Yahweh worship: Explains that Israelite monotheism has roots in Canaanite religion – Yahweh was originally one of the Canaanite gods under El, later equated with El as “God Almighty”.

Wikipedia – Origins of Palestinians: Notes genetic studies showing Palestinians (and other Levantines) derive the majority of their ancestry from Bronze Age inhabitants of Canaan. Also cites early Zionist leaders (Ahad Ha’am, David Ben-Gurion) who acknowledged that Palestinian peasants were likely descendants of ancient Hebrews/Canaanites, calling them “blood brothers” – a view later suppressed for ideological reasons.

Al Jazeera – Golda Meir’s 1969 quote: “There were no such thing as Palestinians… They did not exist” exemplifying the genocide of indigenous identity and tribes in Gaza and the West Bank.

Kurdish Peace Institute – History of Kurds in Palestine: Explains how the Islamic Ayyubid Dynasty and the subsequent Ottoman Empire, which rose to prominence in Anatolia, settled Kurdish tribes in Palestine. Kurds became the largest minority in certain parts of Palestine, such as Hebron. Context: Palestinian clans and leaders with these origins are currently collaborating with foreign governments and intelligence agencies to challenge the indigenous Palestinian claim to the land.

Al Majalla – “Palestinian Stories” digital archive: A 2023 initiative using an online platform to reunite Palestinian diaspora families and safeguard cultural legacy, illustrating the power of technology to preserve identity.

QUNO (Quaker UN Office) – Indigenous rights and Palestine: Highlights solidarity between Palestinians and global Indigenous Peoples, noting that despite UN declarations (UNDRIP) affirming their rights, Bedouins face ongoing violations (marginalization, evictions from ancestral lands). Emphasizes need for concrete steps so both Indigenous Peoples and Palestinians can exercise their rights.

Each of these sources reinforces a part of the picture: that the people of Canaan contributed mightily to human culture, that they survive in today’s Palestinians, that their identity was marginalized by narrative and power, and that now is the time to set the record straight.

In supporting the recognition of the indigenous Canaanite identity, we are aligning historical truth with the pursuit of justice. It’s a long overdue correction of the story – one that we have the privilege and responsibility to help write. Let’s ensure that the next chapters for Palestine's descendants are filled with dignity, empowerment, and hope, with the world as a witness that says:

We see you. We remember who you are. And we stand with you.