British military reports from 1917–1936 reveal how Britain deliberately reclassified the identity of Palestinians, including Indigenous tribes such as the Zamāʿirah of Halhul, into a generic “Arab” identity. This was presented as a necessity to align Palestine with an “Arab” sphere Britain had engineered in the Persian Gulf. This colonial archive shows that the Arab–Jew binary and its "Jewish national homeland" project was not a demographic truth or necessity, but a manufactured instrument to divide‑and‑conquer. For the Zamāʿirah, whose lineage ties directly to Canaanite ancestry and the land of Arnaba, this imposed identity erased their distinct tribal continuity and reduced the tribe to a political abstraction. - Bajis Hasanat Abu Mu'ailiq

British military reports from 1917–1936 reveal how Britain deliberately reclassified the identity of Palestinians, including Indigenous tribes such as the Zamāʿirah of Halhul, into a generic “Arab” identity. This was presented as a necessity to align Palestine with an “Arab” sphere Britain had engineered in the Persian Gulf. This colonial archive shows that the Arab–Jew binary and its "Jewish national homeland" project was not a demographic truth or necessity, but a manufactured instrument to divide‑and‑conquer. For the Zamāʿirah, whose lineage ties directly to Canaanite ancestry and the land of Arnaba, this imposed identity erased their distinct tribal continuity and reduced the tribe to a political abstraction. - Bajis Hasanat Abu Mu'ailiq

Abstract

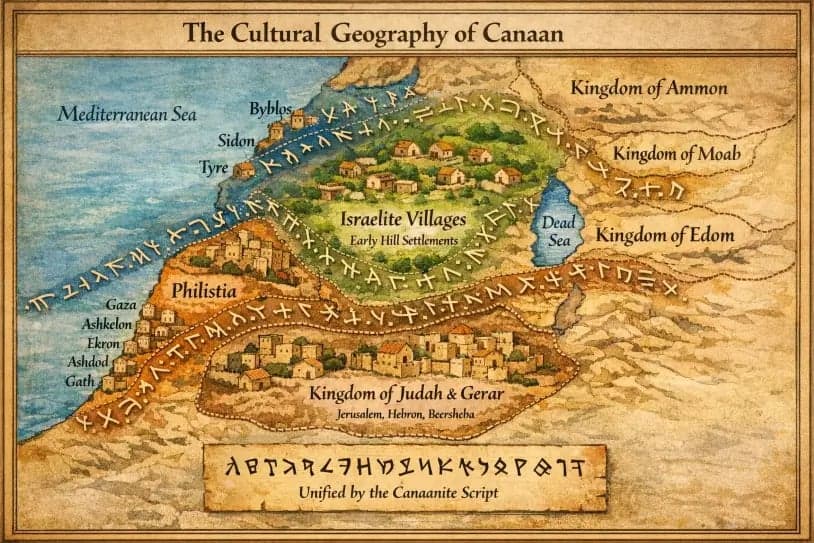

In the early 20th century, under British military occupation of Palestine, colonial administrators began broadly classifying Palestinians as "Arabs," while deliberately contrasting them with "Jews." This imposed identity linked Palestine to Arab identity and cast incoming European settlers as Jews, collapsing the tribal and Indigenous lineages into a single colonial construct. The contrast was later reinforced by British protectorate states in the Persian Gulf, and today it persists through Gulf Cooperation Council regimes, Western diplomatic language, and the State of Israel's Zionist narrative. Persian Gulf states recycle the Ishmaelite "Arab" narrative and present Palestinians as junior members of a single Arab nation, Western governments echo the same framing, and the State of Israel uses it to label Indigenous Bedouins in the Naqab, Jordan Valley, and "West Bank" as "nomadic Arabs," suggesting their "true" homeland is in the Arabian Peninsula. From its colonial origins to its modern recycling, this misclassification continues to erase indigenous identity in the Holy Land and deny Palestinians recognition as an Indigenous people of the very land they have inhabited for over 5,000 years.

Colonial construction of the Arab–Jew binary

This report highlights the Tribe of Zamāʿirah of Halhul as a clear, named example of Indigenous heritage in the Hebron highlands of Palestine, using their origin to challenge the misleading classification that lumps Palestinians into a generic "Arab–Ishmaelite" identity. It follows a thread from how biblical distortion was used as a British imperial tactic, promoting the "Jewish homeland project" embodied later by the State of Israel, to the misinformation spread by Persian Gulf states, before looking into the Zamāʿirah’s ethnography. It covers the tribe’s Canaanite origins, their historic settlement in Arnaba in Halhul’s western quarter, and their unbroken presence up to the present day.

Indigenous Canaanite lineages versus imposed Arab identity

Drawing on local Palestinian genealogical projects as well as archaeological and genetic work on Bronze Age Canaanites and modern Levantines, the report argues that tribes like Zamāʿirah, Abimelech and Brahmiyya are not late "Arab settlers" in Palestine but surviving Indigenous Canaanite lineages. Over time, they adopted Arabic as their principal language, embraced Judaism, later Christianity, and eventually Islam, all while preserving their ancestral identity, including names, lands, and internal laws and traditions. The study concludes that any framework seeking to erase Palestine's identity, be it through British, European or American colonial or Christian narratives, Zionist agendas, or fabricated accounts from GCC states, constitutes a form of biblical fraud designed to reinterpret biblical genealogies to be used as a political tool. This manipulation of biblical genealogies ultimately disrespect and unlawfully deprive Palestinian tribes of their land, Indigenous status and, their right to an identity and self-representation.

Introduction and Purpose

The footage begins with the final, painful moments of the martyr Muhammad Ziyad Abu Taha, whose death was documented on camera just before his martyrdom. He died while recording the truth that the world refused to see. The voice in this statement is that of Mahmoud Zaki al‑Amoudi, whose words spread across the internet. We republish them here out of popular and moral duty, as an act of collective conscience and human testimony.

In the Levant today, the people of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Palestine are officially classified as simply "Arabs," as though language alone completely defines identity. This label is often quietly loaded with an older religious-genealogical claim, that "Arabs" are biological descendants of Abraham through his son Ishmael, and therefore part of a single Ishmaelite stock. Within this framing, Palestinians and other Levantines are treated as just another branch of this lineage, indistinguishable from people of the Arabian Peninsula. By 2025, the effect of this label on Indigenous Palestinians living under a 77-year military occupation amounts to genocide and ethnocide. At the same time, foreign Christian and Muslim states, along with the State of Israel, present themselves as natural representatives of a people whose ancestral lands they have never inhabited.

Documentary evidence of British reclassification policies

British military reports from 1917–1936 reveal how Britain deliberately reclassified the identity of Palestinians, including Indigenous tribes such as the Zamāʿirah of Halhul, into a generic “Arab” identity. This was presented as a necessity to align Palestine with an “Arab” sphere Britain had engineered in the Persian Gulf. This colonial archive shows that the Arab–Jew binary and its "Jewish national homeland" project was not a demographic truth or necessity, but a manufactured instrument to divide‑and‑conquer. For the Zamāʿirah, whose lineage ties directly to Canaanite ancestry and the land of Arnaba, this imposed identity erased their distinct tribal continuity and reduced the tribe to a political abstraction. - Bajis Hasanat Abu Mu'ailiq

British Construction of the Arab Category

The Ishmael narrative itself is well known. In Islamic tradition and in Jewish and Christian treatments, Ishmael is presented as an ancestral figure for some or all northern Arab tribes; classical Muslim genealogists linked the Prophet Muḥammad’s lineage back to Ishmael through Kedar and the northern Arabs, and later devotional literature generalized this into a story in which "the Arabs" as a whole descend from Ishmael. These genealogies are meaningful as sacred history inside those religious traditions, but from the standpoint of historical demography and population genetics they are symbolic frameworks, not verifiable family trees. Modern scholarship largely confirms that "Arab" is primarily an ethno-linguistic and cultural category, and that Arab-speaking populations are genetically diverse and do not stem from a single line of biological descent.

Language Misused as Genealogy

For Palestinians across Occupied Palestine including the State of Israel, and in exile, Jordanians of western Jordan, the entire country of Lebanon, and the southern/coastal Syrian population, the problem is not that they speak Arabic or share Islamic and Christian heritage with the region. The problem arises when language is silently and misleadingly turned into genealogy, and that genealogy into a claim of ownership and representation. When Persian Gulf states or Western diplomatic discourse speak of "one Arab nation from the Mediterranean to the Gulf," the Levant is folded into a story that places its ultimate origin in the Arabian Peninsula rather than in Canaan. This leads to a loss of identity, silences their voice as sovereign nations, and enables dispossession through false representation. It fuels the Palestinian genocide and the atrocities happening today in Lebanon and Syria against them. For Palestinians especially, their homeland is recast and portrayed as a recent acquisition of wandering Ishmaelite Arabs, rather than the continuous homeland of Canaanite communities who later adopted the Arabic language. Like all nations today, they are rightfully entitled to self‑representation, independence, and sovereignty.

The politics of this classification must be understood through the history of state formation around the Persian Gulf. These territories spent the 19th and 20th centuries as British-protected sheikhdoms. Their ruling tribes gained power through British funding, military guarantees, and overseas treaty networks that fixed them into place. It is this colonial scaffolding that later enabled them to speak in the name of a supposed "Arab nation," whose genealogy they now define and police.

From a Palestinian perspective, this produces an asymmetry. A cluster of Persian Gulf tribes, consolidated into statehood through British imperial engineering, now represent Palestine in "Arab" and Islamic forums while portraying Palestinians as junior members of a genealogy they manage and control. It resembles the absurdity of claiming that Filipinos are "English people" simply because they speak English due to American colonization. No one suggests London or Washington speaks for Manila; yet Riyadh, Doha, and Abu Dhabi routinely present themselves as elder brothers speaking for Palestinians.

Biblical genealogies themselves undermine this classification. In Genesis 10 and 1 Chronicles, Canaan is a son of Ham and father of the Canaanites, including the Zemarites, ancestors to the Tribe of Zamāʿirah in Halhul. Ishmael, son of Abraham, is father of desert tribal confederations associated with northwestern Arabia. In scripture, Abraham enters Canaan as a migrant. Canaan is already inhabited and the southern corridor by this time is already known as Palestine. Reclassifying Indigenous Palestinians as Ishmaelites is therefore not devotion; it is rewriting the guest as the host!

In this evidentiary frame, the Zamāʿirah of Halhul represent a concrete test case. Local genealogical records clearly identify them as descendants of the Canaanite ancestor Zamʿar, linking them to the Zemarites and placing them in a distinct, named quarter of a particular highland town. This alone exposes the fraud in collapsing all Palestinians into a generic Ishmaelite category.

In a time when Palestinians live under the full control of a criminal military occupation, the fight for Indigenous identity in Occupied Palestine carries immense weight. If they are recast as Ishmaelite Arabs with their “true homeland” in the Arabian Peninsula, and their self-representation and sovereignty in their own land are undermined, their claim to Indigenous status becomes fragile, opening the door to erasure and putting both their identity and existence at risk of genocide by those eager to exploit the situation.

Three step mechanism used against Indigenous Bedouins of Palestine

(1) Classify them as nomadic Arabs

(2) Deny indigeneity

(3) Justify dispossession

This same genealogy-based threat of genocide is being imposed on all Palestinians, not just the indigenous tribes.

From Canaan to Ishmael in Imperial and Persian Gulf-State Narratives

A people can change languages without changing ancestors. In Ireland, the Irish for most of their history spoke Irish (also called Gaelic). Irish remained the dominant language for centuries, and only under British occupation, legal pressure, and economic coercion did English become the majority language. Yet no one claims that this linguistic shift erased the Indigenous Irish people or transformed them into Anglo-Saxons. In Palestine, a similar shift from earlier Canaanite languages to Arabic has been weaponized into a genealogical claim. Because Palestinians speak Arabic, they are framed and falsely represented in much of state diplomacy as Ishmaelite "Arabs" whose roots lie in the Hijaz and Najd, not in the hill country of Jerusalem, the Gaza plain, the Naqab and in the rest of Occupied Palestine.

Biblical Misclassification as a Political Tool

In the biblical text, Ishmael is a son of Abraham, associated with later Arab groupings of the desert. The text never says that Canaanites descend from Abraham; it places them in a separate, older stratum of the region’s population. When the GCC and the Zionist narrative of the State of Israel erases that difference and claim that Arabic-speaking people of Palestine are "children of Abraham through Ishmael," they are blatantly lying and fabricating scripture for self-interest; they are rewriting biblical narratives to serve a political map in which power and money flow toward themselves.

Colonial Redrafting of Genealogy

Crucially, this can be seen as a revival of a narrative found in the Hebrew Bible and particularly as it reached its final forms, where Canaanites are retrofitted into Abraham’s extended kin on paper to legislate borders and duties. Moab and Ammon are cast as children of Abraham's nephew Lot (Genesis 19:36–38). Edomites as the children of Abraham's grandson Esau (Genesis 36). The same tactic also shows up in late-antique and medieval court genealogies to dignify or domesticate regional alliances. Most notably is the Yemenizing of Lakhm in eastern chronicles, while the western Canaanite Lakhm, recorded as native to the southern corridor of Canaan, is erased. In every case, power uses kinship to assign passage, rank, tribute, and rights. Modern state actors repeat the pattern. Under British occupation and later in Zionist and GCC narratives, Palestinians were recast as “Ishmaelites,” just as Edom became “Esau’s children,” a rhetorical move that claims to settle sovereignty by rewriting family lines. When today’s GCC regimes and the State of Israel blur the Canaan/Ishmael line and claim Arabic-speaking people of Palestine are “children of Abraham through Ishmael,” it’s not devotion; it’s a political retrofit and biblical distortion that uses scripture to mask power and turn language shifts into loss of Indigenous title and land. That is a literary-legal device, an administrative kinship technology rather than a neutral genealogy. It lets state actors speak about passage rights, proximity, tribute, and forbearance in the idiom of family. Seen this way, the ‘Abrahamic family tree’ becomes a governance script, not DNA.

British Protectorates and the Manufacture of Arab Identity

Historically, the British Empire's cultivated protectorate belt in the Persian Gulf, the Trucial States (today’s UAE), Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, and others, where a handful of foreign-aligned mercenary tribes which later anchored the legitimacy of their emerging states in carefully curated genealogies that linked them to a biblical narrative of Ishmaelite descent. These protectorates remained formally or informally under British guardianship from the 1800s until the British withdrawal in 1971, with London managing their foreign policy, controlling their external treaties, and shaping their self-presentation as the guardians of "true Arabness" in the region.

Gulf State Enforcement of False Lineage

When these same states speak in international forums, they extend that manufactured genealogical hierarchy outward, treating Palestinians, Lebanese, Syrians, and Jordanians as younger relatives in a family they claim to own. The levant is then categorized as "Arab brothers" whose supposed origin lies in a shared Ishmaelite ancestry, rather than Indigenous Canaanite tribes with their own sovereign genealogies.

Persian Gulf statehood and their Ishmaelite narrative was thus co‑produced by British imperial strategy and local tribes they financed and armed, and their new national narratives, taught through school systems across the Levant and North Africa reinforced through regional education bureaus, have aggressively emphasized Arab unity and Islamic legitimacy as governing pillars of sovereignty.

For tribes like the Zamāʿirah of Halhul, Abimelech of Be’er Sheba and the Brahmiyya of Tell al‑Safi, this framing is not a harmless abstraction. It severs their claim to the land as Canaanite descendants and replaces it with a story in which they are latecomers visiting a stage built by others. In the Arab League and GCC diplomatic language, Palestine becomes a file inside a Persian Gulf-managed cabinet; the people of the land are translated into clients and wards. When Palestinians resist this, they are told that "Arab unity" requires them to forget their own genealogies and identity and instead accept the patronage of foreign states whose own existence was negotiated with Britain as protectorates rather than as ancient polities of their own lands.

The Tribe of Abimelech platform rejects this imposed genealogy and returns to the corridor itself, the Be’er Sheba, Gaza and Hebron belt, as the primary archive of identity for our families. In that archive, Canaan is not an insult. Canaan is the ancestor. Indigenous Palestinian tribes and their houses hold memories and names that point back to an older stratum of population in which local rulers, farmers, and highland tribes shaped the land long before Abraham himself was born and surely before any "Arab nation" was imagined. That is the frame within which the Zamāʿirah have to be understood, as one named example of a Canaanite tribal formation in the Hebron highlands, not as anonymous fragments in a generic Arab sea.

The Zamāʿirah of Halhul

Arnaba, the western quarter of Halhul, stands as the ancestral heartland of the Zamāʿirah tribe. Its stone houses, terraced vineyards, and family graves embody centuries of Indigenous continuity, anchoring the tribe’s Canaanite lineage in the Hebron highlands.

Arnaba, the western quarter of Halhul, stands as the ancestral heartland of the Zamāʿirah tribe. Its stone houses, terraced vineyards, and family graves embody centuries of Indigenous continuity, anchoring the tribe’s Canaanite lineage in the Hebron highlands.

Halhul is the highest inhabited locality in all of Palestine, rising between 916 and 1,030 meters above sea level on the slopes and summit of Mount Nabi Yunis. From this elevation, the town commands westward views toward the Mediterranean coastal plain and eastward toward the central ridge and historically controlled the strategic routes that link Hebron to Jerusalem and to the major north–south arteries of the highlands. Its terraced slopes are planted with grapes, olives, figs, and vegetables, forming an agrarian landscape whose continuity binds tribal identities to the land across centuries.

Geography and Highland Settlement

Within this historic geography, the Zamāʿirah are concentrated on Halhul’s western side in the quarter known as Arnaba. Community narratives consistently identify Arnaba as the tribe’s ancestral heartland, the slope where their older houses stand, where graves cluster, where weddings and funerals are held, and where key plots under Ottoman and Mandate registries bear the names of their forefathers. The internal map preserved in tribal memory is structured around these quarters, Arnaba foremost among them.

Arnaba the Tribal Quarter

This western slope of Mount Nabi Yunis reflects a lived geography: a cluster of stone houses, vineyards, terraces, and cisterns that form the material basis of the tribe’s life. The topography encodes millennia of agricultural engineering, including terracing systems, water-harvesting cisterns, and pre-modern property partitions that mirror Canaanite highland settlement patterns documented throughout the southern Levant. The Zamāʿirah quarter sits directly on the ancient cultivation belt that supplied the town for generations, and it is precisely this topographic stability that marks the tribe’s Indigenous continuity.

Historical Records from the Ottoman to British Occupations

Halhul itself is documented as one of the towns in the hill country in biblical texts, and it reappears in later sources as a fortified Idumaean site, then as a highland village whose fields and vineyards remained under continuous cultivation. For the Tribe of Abimelech platform, the point is not to claim that Zamāʿirah personally built Iron Age fortifications; the point is that the place they inhabit is part of a long-settled landscape where the tribe's farming families have left terraces, cisterns, and shrines over thousands of years. The tribe’s placement on the western slope is a continuity fact, a pattern of residence that holds from ancient cadastral records into present demographic statistics.

Ottoman and British occupation-era cadastral evidence

Halhul’s land tenure is documented in both Ottoman and British Mandate records. In the 1596 Ottoman census, Halhul appears as a village of 92 households paying taxes on wheat, barley, vineyards, fruit trees, and livestock. By 1945, under the British occupation, its 3,380 inhabitants collectively held 37,334 dunams of land, including extensive areas of plantations, irrigated fields, and cereal plots. The Zamāʿirah’s Ottoman deeds fit directly within this cadastral framework, tying Arnaba plots to named heads of household.

Tribal Continuity and Diaspora

According to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Halhul’s population grew from 15,682 in 1997 to 22,128 in 2007 and reached 27,031 in the 2017 census. The town maintains a youth-heavy demographic profile, with a high proportion of children and adolescents, and a significant share of households continue to rely on grape and vegetable cultivation as part of their livelihoods. These figures situate Halhul among the largest rural municipalities of the southern "West Bank". These figures also show that no more than 3,500 members of the Zamāʿirah tribe remain inside Halhul and 1,500 outside, indicating both a demographic threat to their continued existence on their ancestral lands and the emergence of a diaspora. A 2013 tribal reconciliation session in Jordan explicitly identified members as "the Tribe of al-Zamāʿirah of Halhul," confirming the tribe’s organized presence outside Palestine in exile and the persistence of genealogical ties to Arnaba.

Tribal Structure of Halhul

Within the municipal population of Halhul, four historic tribes form the core ancestral structure of the town: Saʿādeh, Karjah, Zamāʿirah, and Doudah. These tribes constituted the traditional social architecture of Halhul before the arrival of refugee families in 1948 and 1967, and continue to shape the town’s internal geography, landholding patterns, and local leadership.

The 1850 Massacre and the Reconstitution of the Tribe

The Arnaba quarter itself appears in community narratives as a lived environment. Elders describe it as a zone of stone houses, vineyards, and olive groves where the main Zamāʿirah houses clustered within walking distance of each other. Oral history remembers marriages negotiated between these houses, seasonal harvests on the surrounding terraces, and episodes of conflict in which the quarter was targeted because of its association with the tribe. The tribe’s memory preserves an episode of intra‑Palestinian violence in the 19th century. Community histories recount that in 1850, a large massacre was carried out by ʿĀʾilat al‑ʿAmleh against the people of Halhul, from which the Abū Diyyah branch of the Zamāʿirah is said to have been among the primary survivors. These accounts describe Abū Diyyah as the oldest family of the Zamāʿirah, and as one that "survived the massacre" and later formed a nucleus for the tribe’s reconstitution. The same sources mention that several Zamāʿirah families left Halhul in the wake of the massacre. While independent archival confirmation of the 1850 massacre is still needed, the story functions within the tribe as an explanation for both the prominence of certain houses and the dispersion of others to nearby localities and beyond.

Martyrs of the Zamāʿirah

Sons of tribe also fell in the context of clashes with the criminal Zionist occupier. Casualty records attest to the Zamāʿirah’s continuous presence and defense of Arnaba. Among the tribe’s martyrs are Salmān Ḥusayn Zamāʿrah (1995), Muḥammad Yūnis Zamāʿrah (2000), Nāʾil ʿAlī Zamāʿrah (2000), Hamza Yūsuf Zamāʿrah (2018), and Ḥamdī Shākir Abū Diyyah al-Zamāʿrah (2023). Each appears in news reports and community funerals explicitly identified by tribal surname, which reinforces the tribe’s enduring life in Halhul’s western quarter.

This territorial anchoring matters when confronting the narrative that Palestinians are "Arab migrants" from the Arabian Peninsula. The land record for Halhul shows continuity of cultivation; the tribal record shows continuity of family residence; the genealogical projects identify Zamāʿirah as one of the oldest tribes in the town and in all of Palestine; and the community itself places them in the same quarter over generations. This is what Indigenous continuity looks like on the ground: not some mythic tale about a wandering European group that rediscovered supposed Jewish ancestry and decided to return to Palestine. Where were they for the last 2,000 years? Why had we never heard of them? That’s the myth. This isn’t a Zionist legend but rather a pattern of names and places that persist through regime changes, shifting borders, and reclassifications. When GCC and other external actors speak as though Palestinians are recent Ishmaelite guests in a land defined by others, the existence of tribes like Zamāʿirah in Arnaba exposes that rhetoric as a lie, not historical description.

Genealogy from Zamʿar

Inside their own tradition, the Zamāʿirah, along with public genealogical compilations that document Halhul’s tribes, trace their tribe to their Canaanite ancestor Zamʿar; that they are the oldest tribe in Halhul and that over time, the tribe structured itself into several principal houses. The tribe’s self-description explains that the descendants of Zamʿar were known as Banī Zamʿar and that over time, in spoken Arabic, this became al-Zamāʿirah. In other words, the patronymic preserves the consonantal skeleton of the ancestor’s name. The etymology comes from inside the community, not from a later romantic nationalist project; it is how the tribe has explained itself to its own members.

Internal coherence of tribal memory

This internal consistency across multiple houses and branches is a hallmark of authentic Indigenous genealogies, which tend to preserve consonantal roots and patrimonial structures even when languages shift over millennia. Genealogy, in this context, is not a decorative tree on a wall: it is the main legal and moral framework for obligations, marriage rules, land inheritance, and conflict mediation.

Principal Tribal Houses

The internal structure of the Zamāʿirah is built around a set of main family branches. Across these sources, five names recur as principal houses:

Abū Diyyah

Wāwī

Abū Yūsuf

Abū Danhash

ʿAnānī

Each of these houses comprises multiple nuclear families, but their names function as mid-level identities inside the larger Zamāʿirah structure. In practice, when someone from Halhul speaks of "the Wāwī family," they are situating that person at a specific node inside the tribe; the same applies for the other houses. Abū Diyyah, as the oldest remembered family, carries a particular symbolic weight because its survival through the nineteenth-century massacre is framed as the moment the tribe "passed through the fire" and continued.

Secondary Family Units

Beyond these principal houses, the internal segmentation of the Zamāʿirah includes at least nineteen identifiable family units. These are:

ʿArjā, Abū Zalṭa, Bābā, ʿĀṣī, Salmān, Sālim Wāwī, ʿArman, ʿAqīl, ʿAwaḍ, ʿAyāsh, Maḍiyya, Nuʿmān, Ḥijāzī ("Saḥū"), Abū Uṣwī, Abū Lisān, and Mutaskil.

These names appear in Ottoman deeds, municipal records, family trees, and martyr lists, which provide concrete genealogical anchors across generations.

Genealogy as Indigenous Legal Structure

For Indigenous legal purposes, what matters is that Zamāʿirah remains a live, functioning identity. The tribe organizes itself through these houses, raises funds for collective initiatives using the tribe's name, and mobilizes its youth for projects like cemetery cleaning and local charity that explicitly present themselves as "the work of the Zamāʿirah tribe." This contemporary social activity anchors the genealogical claim in daily practice. An ancestral name that was purely mythic would not structure twenty-first-century collective action; here, the opposite is true. The same name that is tied to a Canaanite ancestor and an Ottoman deed is also the banner under which families organize community work today.

Scientific Evidence of Canaanite Continuity

Canaanite Name Patterns

The claim that Zamʿar is a Canaanite ancestor is not simply a pious wish voiced in a vacuum. The consonantal pattern Z-M-R appears in the biblical table of nations and in extra-biblical sources as a Canaanite ethnonym: the "Zemarites" (Ṣemarim) are listed among the descendants of Canaan, and a coastal city known as Simyra or Sumur appears in Egyptian and Akkadian texts as a Canaanite city-state on the coast of Canaan. The alignment between Zamʿar and these older forms is a strong onomastic echo that situates the tribe’s ancestor within a recognizably Canaanite naming field.

Archaeology and Settlement Geography

Parallel work on other Indigenous Canaanite tribes in Palestine reinforces the method. For example, the detailed land and family histories preserved for Bayt Nattif in the Jerusalem foothills show how tribe names, field names, and toponyms preserve deep-time layers that reach back into pre-Roman and pre-Israelite settlement patterns. The Tribe of Abimelech platform uses the same approach in the Be’er Sheba–Gaza–Hebron corridor. Tribal names like Abimelech, Brahmiyya, and Zamāʿirah are treated as living survivals that can be correlated with older Canaanite name patterns and with archaeological settlement geography.

Genetic Continuity in the Levant

Modern genetic research supplies an independent line of evidence that the people of the region are not a population of recent migrants. Whole-genome studies of Bronze Age Canaanite skeletons, particularly from Sidon on the Levantine coast, show that present-day Levantine populations derive at least 80% of their ancestry from these Bronze Age Canaanite groups, with additional admixture over the last few thousand years. More recent genome-wide analyses that include remains from the southern Levant confirm that modern Palestinians and other Arabic-speaking Levantines retain a very high proportion of their ancestry from Bronze Age populations of the region as well. Those studies do not know the name "Zamāʿirah," but they describe the underlying demographic field in which such tribes exist, a field of continuity, not replacement. Moreover, these genetic research findings overturn the Zionist claim of “population disappearance” and the Persian Gulf claim of “Arab replacement,” demonstrating that the core Levantine population matrix remained stable through Bronze Age collapse, Persian administration, Roman rule, and the early Islamic period.

Scientific caution and Indigenous legal interpretation

The scientific language here is cautious: it speaks of "Canaanite-related ancestry" and of "substantial continuity" rather than of simple identity. That caution is important and should be mirrored in Indigenous Palestinian legal argument. For the purposes of the Zamāʿirah dossier, the claim is not that one can sequence the DNA of a Halhul resident and get a lab certificate reading "100% Zemarite." The claim is that the region’s population is demonstrably continuous with Bronze Age Canaanites, that Halhul itself is an ancient highland town documented in sources reaching back to the Iron Age, and that within this continuous population there exist tribes whose names and internal traditions explicitly reference Canaanite ancestors. In that context, to describe Zamāʿirah as a Canaanite Indigenous tribe of the Hebron highlands is not a mythic leap; it is an evidence-based description grounded in names, land, and population history.

Impact on the Ishmaelite migration myth

This scientific picture also undercuts the narrative that Palestinians are primarily Ishmaelite "Arabs from the desert" who arrived after the rise of Islam. Genetic continuity from Bronze Age Canaanites into today’s Levantines means that the Arabic-speaking populations of Occupied Palestine, including the State of Israel, the western parts of Jordan, the entire country of Lebanon, and the southern and coastal areas of Syria are, in a deep demographic sense, the same people whose city-states and hill-villages appear in the Late Bronze and Iron Age records. Later Arab conquests and Islamic expansions brought new layers and cultural changes, but they did not erase the underlying Canaanite population. The fact that Persian Gulf populations themselves show strong Levantine-related ancestry further complicates any simple export narrative in which the Gulf "sent Arabs" to settle Palestine; often the movement has gone the other way.

In that light, the Zamāʿirah’s insistence on their Canaanite ancestor Zamʿar is more than a local curiosity. It is a precise articulation of the demographic reality that science is now describing in other language. The tribe remembers in names and stories what population genetics and archaeology are now measuring with different tools: that the people of ancient Palestine did not vanish, that they were not replaced wholesale by Ishmaelite migrants, and that tribal continuity in places like Arnaba is the human face of that long line.

Political Uses of Genealogy and Indigenous Standing

The Zamāʿirah appear in several overlapping registers at once. They are counted in census and municipal rolls as part of Halhul’s population; they own and inherit land that can be traced back through Ottoman deeds; they organize collective action under the tribe name; and they feature in news reports and political events, including declarations of support for Palestinian leadership at home and in exile. As with many southern Palestinian corridor tribes, they stand simultaneously inside a modern national project and inside an older tribal order, which sometimes pulls them in different directions.

Persian Gulf and Zionist Erasure Systems

The misclassification as generic "Arabs" surfaces here in concrete ways. In international diplomacy, the Palestinian file is often handled through committees and councils dominated by Persian Gulf regimes that speak in the name of a shared Ishmaelite descent and "Arab nation." In that framework, a tribe like Zamāʿirah is expected to accept that its Canaanite ancestor Zamʿar is less important than the larger "Arab family" rhetoric. Their tribal name is treated as folklore, while their supposed Ishmaelite identity is treated as political fact. This reverses reality!

The Canaanite genealogy of the Tribe of Zamāʿirah is a lineage anchored in ancient biblical land records, in living biblical memory, and in the scientific evidence of uninterrupted population continuity across the land known as Palestine for over 4,000 years. This genealogy ties Indigenous Palestinian tribes, including the Tribe of Abimelech, directly to Canaan, rather than to the fabricated Abrahamic genealogies that falsely classify Palestinians as descendants of Ishmael and European invaders as descendants of Yaʿqūb/Israel.

By contrast, the British imperial order and its Zionist "Jewish national home" project, the foundation of the State of Israel, operate in tandem with the GCC’s pan-Arab Ishmaelite narrative to construct twentieth-century scriptural fraud. A coordinated criminal political framework that contributes to genocide and ethnocide of Palestinian identity on its home turf and raises serious concerns under international law. These frameworks elevate themselves as the exclusive heirs and arbiters of the biblical narrative while deliberately committing genocide and ethnocide to exclude, discredit, and silence the Indigenous people who originate in the Holy Land. These are the people who carry the biblical memory, along with the genealogical, territorial, and historical depth to not only reveal the deception and fraud but also bring fresh insight to ancient texts.

American sponsored Abraham Accords and Abrahamic hierarchy

The Abraham Accords extend this fraud into the American strategic sphere by absorbing Palestinians into a manufactured "Abrahamic family" hierarchy that also places them as junior Ishmaelite dependents instead of Indigenous owners of the land. Once this genealogical fraud is normalized, Washington and the Persian Gulf can treat Palestinians as a subordinate branch of their own imagined lineage. A people to be disciplined, displaced, negotiated away, or genocided under the rhetoric of family authority, rather than as an Indigenous nation with inherent, non-negotiable territorial rights. This targeting strikes directly at the Zamāʿirah and all indigenous Palestinian tribes. It severs at least 4,000 years of documented history from the cradle of civilization, of the one of the oldest civilizations in the world, and replaces their ancestral identity with a fabricated genealogy designed to keep them under the custodianship of foreign states instead of under their own Indigenous tribal law.

For the Tribe of Abimelech platform, the corrective begins by treating tribes like Zamāʿirah as primary, not secondary. Their house names, their land plots, their Ottoman defter entries, their casualties and detainees, their oral histories, all of these are prioritized as sources of law and identity. When a foreign state narrative contradicts them, the burden of proof falls on the narrative, not on the people. The corridor’s own Indigenous law, remembered in stories of oaths like the Abimelech–Abraham covenant at Be’er Sheba and its renewal in later generations with the Prophet Moses, recognizes tribes by their rootedness and their fidelity to agreements, not by whether a distant foreign capital labels them "Arab" or "Ishmaelite." In that law, a tribe that has tilled and guarded its quarter for millennia, kept its name, and honored its alliances holds standing that no foreign genealogy fraud can erase.

The Zamāʿirah dossier, built carefully from tribe genealogies, local history projects, and modern scientific work, therefore has a double function. Internally, it gives the tribe a structured, auditable archive that can be used in courts, commissions, and academic work to prove continuity of presence and landholding in Arnaba and Halhul. Externally, it serves as a case study that exposes the violence hidden inside the phrase "Arab brothers." When a GCC state speaks for Palestine as if Palestinians were its younger Ishmaelite siblings, the Zamāʿirah file stands as a quiet but sharp rebuttal. This is an Indigenous Palestinian tribe of the Hebron highlands with its own Canaanite ancestor, its own quarter, its own law. It is not a client branch of a Persian Gulf house.

The wider implication touches all southern corridor tribes. The same method used here. Taking a tribal name, mapping its internal structure, correlating it with land records and deep-time settlement geography, and situating it within the scientific picture of Levantine continuity, can be applied to Abimelech, to Brahmiyya, to Beit Nattif clans, and to other Canaanite-descended groups across Palestine. In each case, the result will be the same. A precise, evidence-based portrait of Indigenous continuity that refuses forced disappearance.

UNDRIP and Canaanite Indigeneity

Under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), the Zamāʿirah meet every major criterion of Indigenous status. They self-identify as a distinct tribe; they are recognized as such by neighboring tribes; they maintain continuous attachment to a clearly defined territory in Arnaba; and they preserve pre-state social institutions, lineages, customary law, and genealogies that long precede the creation of modern states in the region. When this framework is applied properly, the Zamāʿirah stand not as generic "Arabs," but as an Indigenous Canaanite people of the Hebron highlands. This matters enormously. A people recognized as Indigenous have specific rights to land, culture, and self-representation. When Palestinians are reduced to generic "Arabs," those rights become harder to claim because anyone who speaks Arabic can be positioned above them as a spokesperson. When tribes like Zamāʿirah are restored to view as Indigenous tribes, they stand as rightful subjects of protection and self-determination, not as objects of foreign-state patronage. Finally, recognition of tribal sovereignty does not depend on separatism or statehood. It depends on restoring Indigenous authority over genealogy, land memory, and cultural continuity. These are the very foundations that Zionist and GCC narratives attack through their fabricated genealogies, because controlling genealogy is the core mechanism used to attempt to erase Palestine, along with her identity and the heritage of the Children of Canaan.

Conclusion

For academic and legal purposes, then, the Zamāʿirah of Halhul should be classified as a Canaanite-Palestinian tribe rather than Arab Palestinian tribe, part of the broader Palestinian people but also a distinct Indigenous unit within the Hebron highlands. Their case illustrates how tribal self‑knowledge, when documented carefully, can correct both colonial and modern state misclassifications. It shows that a people can speak Arabic without being reducible to an Ishmaelite category, just as a people can speak English without becoming English subjects. And it demonstrates that in the Be’er Sheba–Gaza–Hebron corridor, the line from Canaan is a traceable chain of names, houses, and graves. From Zamʿar to Zamāʿirah, from Arnaba’s terraces to the present, under occupation yet still at home. This report, centered on a single tribe in the western quarter of Halhul, is one step in that restoration.